The Negley-Gwinner-Harter House on Fifth Avenue in Shadyside was threatened with extinction, but a tireless restorer of historic places and the owners who followed staved off the bulldozers.

In one of Wednesday’s posts, I touched on some of the older, more modest houses that remain a part of the Shadyside fabric. Today, I’m taking a look at five of the remaining palaces from what once was Pittsburgh’s Millionaires Row that stretched along Fifth Avenue from Oakland through Shadyside into Squirrel Hill.

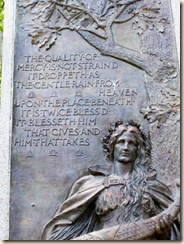

The first entry is the Negley-Gwinner-Harter House, the second oldest surviving mansion on the row, which was built for Civil War veteran and attorney William Negley in the Second Empire style in 1871-72.

Stone contractor Edward Gwinner bought the house in 1911 and soon tapped architect Frederick Osterling to design a three-story addition, a porch and the interiors of some rooms to update a home that was then less than stylish. The work was complete by 1923.

Dr. Leo Harter began years of renovations when he obtained the house in 1963, but a 1987 fire badly damaged the third floor and nearly signed the structure’s death warrant.

But days before it was to be torn down in 1995, Joedda Sampson, who is known for her work restoring historic places in Pittsburgh, came to the house’s rescue.

After a year and $1 million, Sampson worked her usual magic on the place, which also boasts great landscaping, a fountain in front and patio inside its cast-iron fencing.

The Negley-Gwinner-Harter House has passed through several owners since Simpson’s intervention, but it never fails to impress and charm me when I walk past.

Next door is the Moreland-Hoffstot House, which was completed in 1914. Built for Andrew Moreland, who held various positions in the iron and steel industry in the early 1900s, he lived there through 1926.

When Moreland married into the family, White’s work in Newport was the model.

Henry Phipps Hoffstot bought the house in 1929 and lived there until his death in 1967. He served as vice president of operations of the Pressed Steel Car Co. from 1918 to 1933 and president of its subsidiary, the Koppel Industrial Car and Equipment Co., from 1918 to 1936. His son, Henry, extensively restored it. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

Click for more details on the Moreland-Hoffstot House.

In 1919, John H. Hillman Jr. bought the property and commissioned architect Benno Janssen to design a new house. But Hillman decided to remodel the house instead. E.P. Mellon, architect and Mellon heir, encased the old house in limestone. It remained in the Hillman family until 1975 and now houses condominiums.

Part II: Sunnyledge, Howe-Childs Gate House and Mudge House.